TheBus Transit Tracker

The TheBus Transit Tracker is a mobile-first web application that is intended to replace the current official “DaBus” and “DaBus2” mobile apps. This means that it is a website “app” deigned specifically for mobile use, but that can still be used on a laptop or desktop. It presents realtime vehicle tracking information for city busses.

When I started this project in December of 2015, the City & County of Honolulu had a published mobile application in both the Apple App Store and the Google Play Store, named DaBus. This was the “official” native mobile app for tracking busses. After having used the app for a while, I found some “quirks” with the app that I felt were either unprofessional, outdated, or broken.

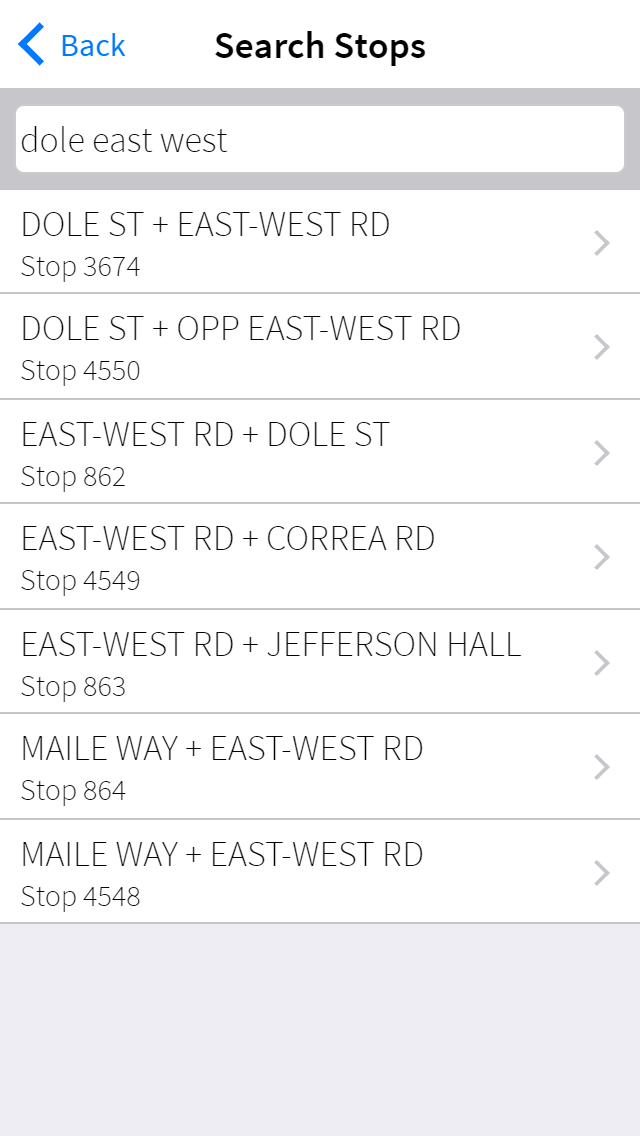

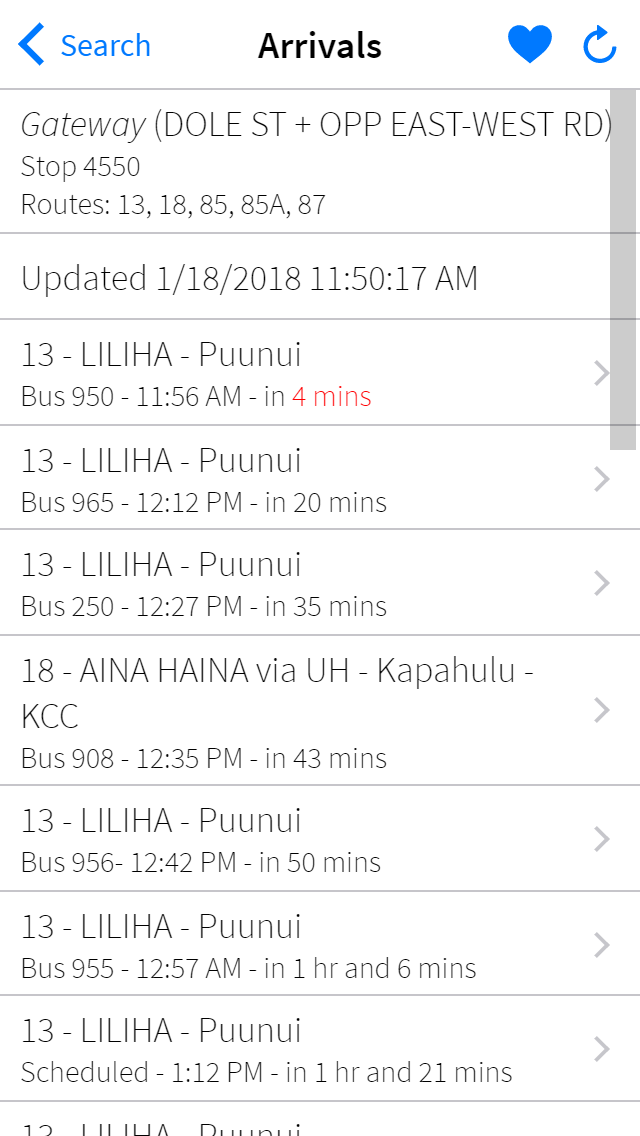

For instance, trying to find a stop by it’s street name (using the names of the streets that the stop is on), can be very difficult. According to the DaBus FAQ, the best way to find a stop is to type the first few letters of the street. This can be bad, especially if that street has many stops on it. Take the stop on South King St and Punchbowl for example. Performing a search for king punchbowl returns no results. In order to find this stop, one would have to search for king and scroll through the 100+ stop results to find it. Even searching for the full stop name, verbatim (like S KING ST + PUNCHBOWL ST), fails, yielding no results.

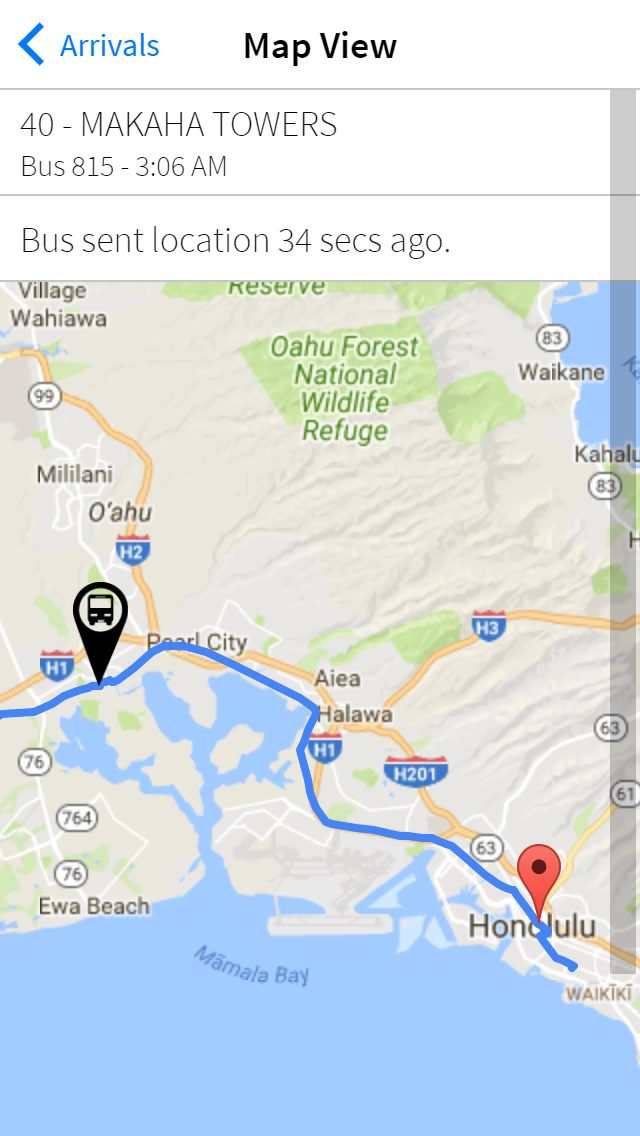

Additionally, the “official” way to get transit directions is to use Google Maps’ transit feature. That means that users have to open Google Maps to get directions, and then open DaBus to see where the bus is. And if that user happens to forget his/her route, they have to go back to Google Maps, and then switch yet again to DaBus to check the buses. I want to be able to unify this experience in a single app. These reasons, among a few others, inspired me to create my own transit tracking app that included these improvements and features.

Sometime in 2016, the C&C of Honolulu published a second mobile application, called “DaBus2”, that updated the theme to match iOS 7 - 9, and added the ability to give nicknames to stops. However, the main issue for me - the search function - has not improved.

This project is the second significant project that I created that used a Node.js back-end. From this project, I learned a lot about user interface layout, usability, and design. This is also the first project of mine that fully embraced ECMAScript 6 features such as Promises and the new block-scoped “let” keyword.

I am the sole developer of this project, so I am responsible for creating all of the icons used, the back-end server, and the front-end client design. The back-end is built in JavaScript using Node.js. The front-end is dynamically generated using an object-oriented approach, using instances of “view” classes. I wanted to avoid using jQuery, so this front-end is powered by a simple framework that I created, called CommonLib. Client-server communication is accomplished by utilizing websockets, implemented using socket.io. This application uses the public OTS TransitMaster API and OTS-provided GTFS (General Transit Feed Specification) data to present realtime vehicle tracking and arrival data.

You can check out a public deployment of the project at https://thebusapp.herokuapp.com/ (might take a minute or two to start up if it’s currently shut down).